Magazine Feature Articles

Christopher Austyn: The lifespans of sporting guns built by masters of their craft

It is interesting to speculate over whether any self-respecting gunmaker has in mind the eventual demise of the product of his labours. In view of the many hundreds of hours spent in building a best gun, I think that nothing of the sort will enter his mind. As with any great creative process, the gunmaker, like the artist, will crave only immortality for his work. If this can be accepted as a truth, we can only suppose that the eventual demise of a best gun comes about as the result of the natural dissolution of its component parts.

Factors in determining the longevity or otherwise of a best gun will be discussed later. Meanwhile, it is instructive to examine some examples of guns which have outlived many human generations—a curious thought bearing in mind that a best gun is usually only ever dedicated to a single owner. The first of these truly ‘great’ guns exists in the collection of the Royal Armouries, formerly housed in the Tower of London.

This gun was built in 1537 for Henry VIII and it has, therefore, outlived 24 monarchs and rulers of the United Kingdom. If we assume that the present world order will continue indefinitely, it is very likely that this gun will outlive many more heads of the British State. The weapon in question is a breech-loading wheel-lock gun which has had its original firing mechanism replaced by a later plain match-lock.

As with many of his contemporary princes, Henry VIII was intrigued by the new mechanical devices of the day, and the arms of war had a particular fascination for him. At his death he had 139 breech-loading guns in his collection. With the exception of its original firing mechanism which was probably replaced through obsolescence, and the original velvet-covered cheek-pad which probably dissolved, the gun remains today essentially as it was in the first years of it age. There are some missing stock elements, the forend has been cut away at the muzzle, and there is the inevitable wear to the surface of the metal, but the gun has survived. It will continue to survive because of its Royal birth and, perhaps more importantly, because of its intrinsic quality.

Another very good example of the longevity of guns is that of a very fine example from the same collection. This flintlock sporting gun dates from about 1685 and was built by the French gunmaker Bertrand Piraube. It is believed to have been a presentation piece given to Charles Lennox, 1st Duke of Richmond and Lennox, by King Louis XIV of France and it exhibits all those characteristics which elevate certain guns to artistic masterpieces.

The lockplate is carved with mythological figures and the gun is otherwise profusely decorated with classical motifs, monsters’ heads and grotesques. Rather more unusually, the barrel is made of silver rather than steel, an indication that the gun was essentially built for presentation purposes and not for normal use.

Other guns in the Royal Armouries collection provide many more examples of survival through centuries for reasons of exceptional quality and provenance, historic and technical interest, but these are all out of the ordinary. More relevant to modern sportsmen are those factors which dominate the life expectancy of a normal best quality gun.

That so many good guns built in the last two centuries still survive is an indication that the essential quality of a gun will guarantee a very long and useful life despite hard use, and the current auction market for guns is absolutely dependent on this factor. In my own sales virtually all the guns are classified as either vintage or veteran, with a very few having been built in the last two or three decades. The frequency of a factor at auction, whether it is a certain type of gun, an unusual feature or a fault, is a very useful indicator of what can be widely applied elsewhere. So it is also with factors that restrict the life expectancy of a gun.

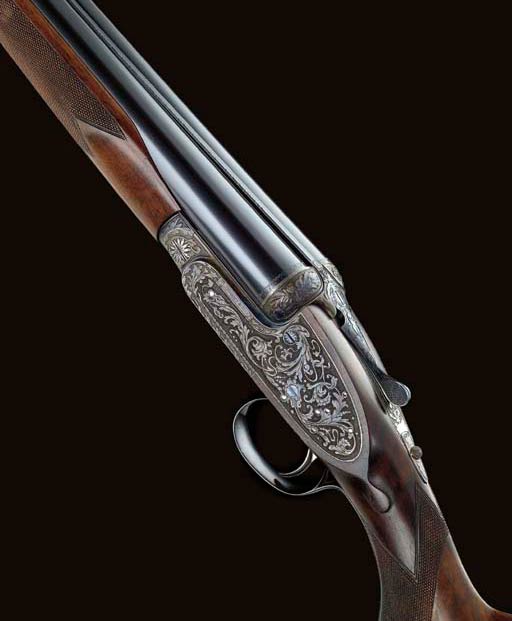

In general, and with periodic maintenance—oiling and cleaning—a gun will last for ever, and the only threats to this arise from use, abuse and accidents. In, for example, a best quality sidelock gun, the strongest component in its overall structure is the action-body which links the stock and barrels, and which is the receptacle for the lockplates and lockwork. The development of the action-body as we know it today has taken place over a very long period of time and the design which has been in use since the 1880s has, with certain stylistic differences from maker to maker, provided a perfect combination of strength, function and weight. An action can be dropped, dented, or worn smooth, and it will still continue to function.

As with all exceptionally strong and potentially flawless entities, however, the only thing that will threaten the life of an action-body is a potentially devastating one. The bar of the action-body or that part which is cut away to take the lumps of the barrels joins the face of the breech in something of a right-angled joint. For obvious reasons, this is the point at which most stresses on the action-body occur when the gun is fired, as the bar and the breech will strive to move away from each other. Early sidelock and boxlock guns used action-bodies in which the bar and the breech face were joined in a pure right-angle. But the experience of gunmakers and the proof authorities proved that this junction, without any form of strengthening, could lead to fractures along the action-body below the breech face.

While these fractures are sometimes nothing more than cracks in the hardened surface of the metal, there have been cases of action bars splitting away from the breech face itself and this is why the junction between the two has, for many years now, been strengthened by a radial join. It is now very rare for an action-body to fail at this point but it is worth considering the consequences of this, should it happen.

The action-body is arguably the most expensive part of a gun, and with replacement best quality pairs of barrels alone costing up to £10,000 a pair, no more emphasis needs to be made. There is also the much greater issue of safety, the action-body being a little closer to the firer’s face than most of the barrels. Of the other component parts of a gun —the stock, barrels and furniture—only the stock and the barrels present a threat to the use or life of the gun if they are damaged, but both are easier to replace than the action-body itself. The furniture, which comprises the trigger guard, top-strap, safety and so forth, can be damaged or broken but this can be fairly easily remedied.

The major threats to the stock come from extreme wear, oil damage or actual fracture, with a material fracture being the most serious. Sometimes, through many years of application of the wrong type of oil to the stock (linseed oil and other specific stock preparations are the only things that should be applied to the wood) a softening gradually occurs around the head and hand of the stock and this can easily lead to cracking at the weakest point.

Stocks can be replaced, but exceptionally-figured wood is a very expensive commodity and guns that are unusual in having beautiful stocks need even greater care. The barrels of a best gun, or indeed any gun, are susceptible to dents, pits, bulges and, in extremes, actual bursting but as they are also replaceable (but again expensive) they do not really threaten the life of the gun itself. Barrels can also become thin as the result of many years of repair work, and when because of this they become unsafe, they must be replaced.

The actual firing of cartridges through the barrels has a negligible effect on them—lead is so much softer than steel—but it is important to remember that newer steel shot cartridges can materially damage barrels and should be used only in consultation with the gunmaker. I believe that any best gun, when cared for in the proper way, will outlast many generations of users, and as the first two examples illustrate, where there is cause for a gun to be cherished, it may even last for ever.

¶ This article was first published in Country Illustrated magazine. An international expert on modern sporting weapons, the writer was head of the department at Christie’s auctioneers when he wrote a series of articles on the subject. He has also written several influential books, and remains one of the foremost authorities.

PLEASE READ: CountryClubuk Club Rules and Terms and Conditions