Magazine Feature Articles

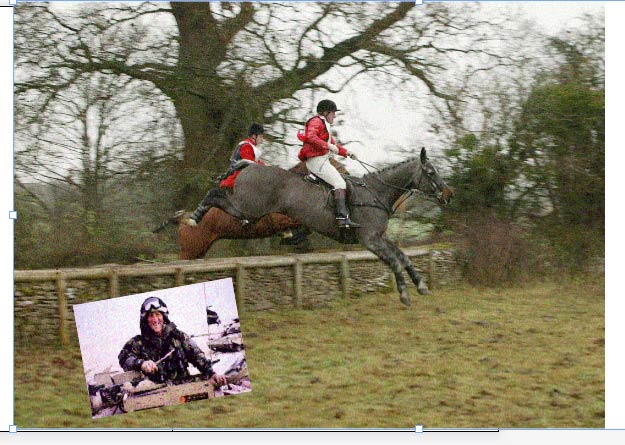

Major-General Arthur Denaro CBE: A hunting horn in the desert

A distinguished officer and foxhunter pays a moving tribute to a paratrooper wounded in action in Afghanistan. He defines, as far as anybody can, the shared qualities that go to making soldiers and sportsmen alike.

By Major-General Arthur Denaro CBE

I knew he was going to fall three strides out, the young cavalry officer who had been weaving around in front of me over the preceding two hedges. I should have known that there was no way round him, as Patrick Beresford and I had walked the course only the day before and commented on what a bad race fence it was—much too narrow.

Sure enough, down he came and we crashed straight into him, my old horse doing a cartwheel, happily throwing me out to the side. Righteously enraged, I delivered a rocket to the unfortunate officer and demanded he give me a leg up so that one of us at least could complete the race. He looked not only battered but crestfallen. He too had wanted to finish.

A week later I listened in awe and respect as a young Parachute Regiment soldier, Lance Corporal Tom, spoke strongly and clearly to a packed congregation in Hereford Cathedral at a carol concert in aid of the Army Benevolent Fund. From his wheelchair he told of the moment he lay down in a sniper’s position to shoot through a hole in the wall of a compound in Helmand, Afghanistan.

Quietly he spoke of the explosion that blew off both his legs and left one arm hanging by a thread. He told of his friends who came to lift him gently on to the back of a donkey to carry him to the helicopter landing site. He told, with a grin, how he kept sliding off, as he had never been a good jockey. He told of the journey from Afghan-istan to the hospital at Hedley Court in England, and all the stops in between. There was never a trace of self pity or bitterness … and finally he told us he could not wait to get back to Afghanistan to sort out the Taliban, who had done this to him.

Where is the link between these two stories? Is it even acceptable to link them? I suppose it is to do with ‘spirit’ and all that this means. I know that Corporal Tom would not mind my drawing some parallels out of these. I will do so by quoting from Pink & Scarlet, or Hunting As A School For Soldiering, by Major-General Anderson, though written 100 years ago, because, as the immortal Mr Jorrocks said, ‘’Unting is the sport of kings, the h’image of war without its guilt and only five and twenty per cent of its danger!’, and ‘spirit’ is what so many of our young have plenty of. Having soldiered and hunted for most of my life, I am pleased to confirm it.

The book starts with a classic quote from Lord Minto: ‘The young officer as he gallops his hack to covert over the rolling uplands cannot but mutter to himself, “What splendid positions for troops! By jove how I should like to defend that farm with its green fields sloping gently to the brook!” Then as the magnificent vale opens out before him he tries to grasp the general lie of the land.

‘He notices the strongly fenced paddocks, the great woodlands on the skyline, the canal in the distant bottom, glittering in the sunshine. He notes the wind, the temperature, the dewdrops on the blackthorn hedges and wonders if there will be a scent.

‘When, late in the afternoon, after a rattling 40 minutes, he turns his horse’s head for home and looks back on the day that has passed, he thinks how like it all has been to scenes in distant lands; memories of the veldt, of thick bush and a hidden enemy, of sweltering days in the desert and the gallant Indian and Arab horses that carried him … and of how well his soldiers fought.

‘He questions himself as to how he has borne himself in the brilliant gallop of the afternoon. Did he always keep his head? Was he flurried when the hard-riding farmer crossed him at the rail? Did he realise soon enough how the good young horse under him was beginning to fail, and wanted nursing, can he tell what other men were doing to the right or left of him? Could he mark the spot on the map where hounds first hesitated or where they finally rolled over their fox? Could he write a good report of it all for his CO?

‘He feels that there is so much to be learned from a day with hounds; he has always placed courage above all things in the hunting field as well as the battle field, but again he has realised that courage alone will not guarantee him a place in the first flight with hounds or in the first rank of distinguished soldiers. The hunting field has taught him the value of a cool head, quick perception of surrounding conditions and power of instant decision; lessons which he hopes and believes will stand him in good stead in many a tight place in the future.’

So what are these lessons I have learned from the hunting field in more than half a century, from those early days in Ireland on a wee Connemara pony; then as a young officer with the South Dorset Hunt under Captain Simon Clarke, and through a lifetime of travelling the Hunts of this great country in the privileged position of a ‘serving officer’.

There was a time when Hunts allowed a visiting young officer to hunt by paying only the cap, and not the normal visitors’ fee. Perhaps we should start this again. I have had the pleasure of hunting with the Bedale and Zetland, when stationed in Yorkshire, and some Shire packs when I was abroad and lucky enough to break away for a day and steal a horse from Melton Mowbray.

I had some brilliant happy days with Sir Watkin Williams-Wynn’s and the Meynell during my time as GOC in Shrewsbury, and enjoyed great sport and friendship from the Duke of Beaufort’s, the Heythrop, the Vale of White Horse and the Cotswold, before, most recently, the Portman and the Berkeley. Now retired, here in our beautiful Herefordshire I have been lucky enough to hunt with the Ledbury, the South Hereford, the Radnor and West Hereford and the Golden Valley. Invariably my hosts have been kind and welcoming, even if some have tried to get this old visitor on his backside. I fear some have succeeded, but I have met great people and made good friends among this wonderful community of hunting comrades.

Some of the lessons are touched on in a letter I wrote to a country magazine when commanding the Irish Hussars in the first Gulf War: ‘In these last few days before we go into battle your magazine continues to give us glimpses of the familiar and much loved world that is so far away at this moment. I keep it in my tank and note with no surprise how many of the skills of the field sportsman are similar to those which we have been honing out here in the Saudi desert these last four months; the foxhunter’s eye for a good line across country; the stalker’s use of ground and awareness of wind direction; the swing and lead that a good game shot perfects; and the patience of a fisherman. Above all, the knowledge of the habits and tactics of the quarry.

‘By the time you receive this letter, our quarry may well have left covert. We would want to bowl him over in the open and then return safely to our loved ones and everything else we have missed in this “lost season”.

Return we did and safely, mostly. I was clutching my grandfather’s old hunting horn which I had taken everywhere with me since being sent to prep school in England, aged eight. I used to blow it quite often in the desert, which drove everybody mad and encouraged them to buy me a tape of horn ‘tunes’ by that excellent huntsman Alastair Jackson. I am no better at it today.

On the day before we crossed into Iraq I was visiting all the squadrons. The Regiment was lined up with the rest of the 1st Armoured Division, over a thousand vehicles in the desert sands, and returning to my tank that evening I realised I had lost my hunting horn. I had refused to consider it a lucky talisman because there was always a good chance I would lose it, but somehow its loss at that moment affected me. Corporal Jack, my great (in many ways) Land-Rover driver, disappeared back into the gloaming from whence we had come, followed our tracks, criss-crossed by all those armoured vehicles, and there, after 10 kilometres, he saw the old hunting horn sticking up in the sand. Happy moment.

A little less than 24 hours later, as we spread out inside Iraq having threaded our way through the 16 kilometres of minefield, and just as I was about to give the order to advance, I saw a silver desert fox lope casually across the sand in front of my tank. ‘Tally ho!’ I ordered, and the boys kicked on right the way up to the Basra road some 300 kilometres to the east.

‘No man takes so readily to soldiering as a sportsman, and particularly a man who rides well to hounds,’ wrote Anderson a little more than 100 years ago, and I have no doubt that the sportsman part still holds true today. By and large, my best officers were talented sportsmen and I remember discussing this with Sir Tasker Watkins VC, PC, QC, when I had the privilege to sit beside this great soldier sportsman at a dinner not long before he died. He was President of the Welsh Rugby Union at the time and we were talking about how many international rugby players in the past had been awarded gallantry medals. ‘It’s their steadiness under a high ball, and their courage in a tough tackle that prepares them so well to do the same in battle,’ he said.

What are the key lessons which still apply today? Professionalism: ‘A sportsman’s instinct makes him naturally a dashing lead-er of a squadron or company, but it requires more than that to be a good commander in modern war.’ I would add that nobody should be so foolhardy nor so arrogant as to consider leading men into battle unless he is utterly professional himself. Discipline: In talking about dress on the hunting field, Anderson says ‘a slovenly dressed officer means slovenly dressed men, and slovenly dressed men mean want of discipline.

Discipline is that which distinguishes soldiers from a mob. It is also that which raises men above themselves and makes them afraid to run away.’ I now wear a tweed coat out hunting, and hope my ratcatcher would not be considered ‘slovenly’. Courage: ‘Hunting will give you the requisite nerve and decision to extricate yourself from a very much tighter fix than a roll with a horse.’ This of course applies not only to hunting but to most contact sports these days, which is why the Army encourages participation in anything with an element of risk. It tests a person, and it is fun. Care:

Several wonderful Lionel Edwards paintings illustrate Anderson’s book, but the two I love best are these: First, of an old man visiting his horse in the stable after hunting and asking his groom, ‘Well Jim, has he fed all right?’ The second is a painting of an officer talking to his men, sitting around a camp fire, and asking them, ‘Dinner all right men?’ Care breeds comradeship, which underpins our fighting spirit. Determination: This brings me back to the beginning, with the young officer so crestfallen and battered, and Corporal Tom, so keen to get back into action.

¶ This article first appeared in Country Illustrated magazine.

PLEASE READ: CountryClubuk Club Rules and Terms and Conditions